Welcome to another blog version of the Game for Thought series (GFT), this is a written recap of Howest DAE’s livestream series that tackles ethically-relevant topics in the games industry and explores the impact & implications of industry developments.

Reason enough for us, here at FLEGA, to communicate these topics and challenges as widely as possible. In this blog recap of the livestream, we’ll break down the most important talking points of the panel, but for those who prefer to watch the entire video, you can find it below.

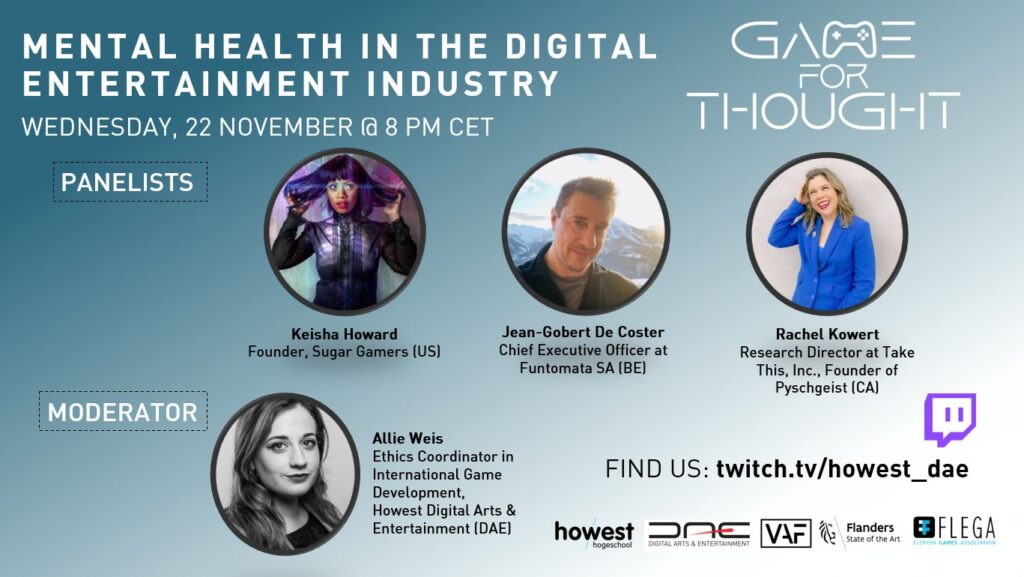

In this Game For Thought panel, we talk about neurodiversity in Games. From what games can mean to neurodiverse people to how they can be developed with this pretty sizeable audience in mind.

In this panel:

- Pierre Escaich, Neurodiversity Talent Program Director at Ubisoft (SE)

- Coty Craven, Project Manager at Descriptive Video Works, Inclusion & Accessibility Consultant (U.S.)

- Lisanne Meinen, PhD Candidate at the University of Antwerp, Neurodiversity & Video Games (BE)

- Alan Jack, Academic Disability Coordinator & Game Design Lecturer, Glasgow Caledonian University (SCT)

- Moderated by Allie Weis, Ethics coordinator at Howest DAE (BE)

Check out the full video here:

How would you define neurodiversity?

Coty Craven: The two automatic things that come to mind are autism and ADHD, but I also tend to think of mental health because there are a lot of ways it can impact the way your brain functions and how you interact with the world.

Pierre Escaich: The term has only been coined by Judy Singer in 1989, so it’s quite recent. It refers to variations in the human brain in terms of social ability, learning, mood and other mental functions but in a non-pathological sense. In fact, neurodiversity may apply to everyone; each of our brains are as unique as our fingerprints.

Neurotypical means that your brain functions closer to that of the average population, but when we talk about neurodivergent people, we mean the ones who stray far from the average. The medical world only tends to focus on where things go “bad” but there are also functions where a neurodivergent person performs much better than the average.

Alan Jack: It’s important to draw the distinction between “neurodiverse” and “neurodivergent” people, the latter is when we are more likely to talk about autism, ADHD, dyslexia or other processing disorders. A lot of people will have some symptoms that come with those disorders, but only to a certain degree. It’s when you combine it with all these other things that it becomes much larger.

Which misconceptions really stand out to you?

Alan Jack: I used to beat myself up for my ADHD symptoms, before I got my diagnosis and the one that always stuck out to me was “autistic people have trouble with expressing feelings”. But as I’ve worked with autistic students and gotten more in touch with my own autistic traits, I’ve begun to understand we experience incredibly intense feelings and because of some processing disorders that tend to come along with it, we display those feelings differently. We connect to other people in a different way.

Pierre Escaich: Someone with ADHD, autism or dyslexia can do all types of job. At Ubisoft, you can find autistic people in almost every job function. A common misconception I dislike, for example, is “someone dyslexic can’t be a game writer”. Dyslexic people have the ability to create stories, to see the big picture, to create connections and you want those kind of talents in your team. As for the issues with reading and writing, there is assistance built in to all the tools we’re using daily.

Lisanne Meinen: Often people will fear having the label that comes with a diagnosis, but it can help people get the accommodations they need to function. A diagnosis doesn’t have to be a bad thing.

Alan Jack: Everyone is facing different internal challenges. Especially when it comes to diagnostic criteria, a lot of it is based on external viewpoints. I don’t like how some get labeled as “high-functioning” or “low-functioning” autistic people, based on their achievements. But you don’t see what’s going on internally and how much energy it costs them to keep up or how much of an impact it has to get the right support.

How can WE advocate FOR neurodiverse employees?

Pierre Escaich: We need to establish psychological safety. This means that people should not be afraid to share their (unfinished) thoughts, and that it should be OK to make mistakes. Making games especially is an iterative process: we’re always making mistakes. You should not be blamed or punished. You should feel safe being yourself.

Coty Craven: One of the worst experiences in my professional life was when I asked for captions and was greeted with reasons why it’s a bad idea and a security risk. So my advice for when you are a lead and you get a request to accommodate for someone: keep your doubts to yourself. The person asking for it should not be made to feel worse than they already do.

Alan Jack: Simply listening to people without judgement is very important!

Lisanne Meinen: It’s good that there are ways to ask for individual accommodations, but it also puts pressure on the person requesting them and requires them to disclose their diagnosis. So my advice is to try and make changes that could benefit everyone. An example would be providing accessibility guides or providing a quiet room which can be used by autistic people, but also for breastfeeding or prayer.

How can people advocate for themselves?

Pierre Escaich: Students (and employees) should not be required to advocate for themselves. The system is broken. We should all be gathered around the same objective: making games. We want everyone to succeed. It’s not a matter of will, but one of skill. Everyone is passionate and committed. So ask yourself what could prevent you from studying, working or delivering results and what can be done to support you.

Alan Jack: Sometimes you do encounter students where it’s a willpower issue. We all have motivation, but sometimes the motivation doesn’t align with the system you are currently in. Honest conversations will go a long way and as a teacher, it’s partly my responsibility to provide the motivation and explain the “why” behind an assignment.

How can we deal with shame?

Lisanne Meinen: It helps to connect with others. Building a community of other neurodivergent students or employees and having a place to discuss among each other can be very helpful.

Pierre Escaich: At Ubisoft, we have an online private channel that serves as a safe place. We recently had a panel about anxiety and someone raised the fact that they needed to know where a dinner was going to take place 3 days in advance so they can plan what they are going to eat, and even a few back-ups. And several people in the audience said “OMG, so I’m not the only one!?”. It’s important to feel that you’re not alone.

How does it impact (small) indie teams?

Alan Jack: Know yourself and know your limitations. I discovered I’m more of a systems designer, and I could never start a company myself. I need a gameplay designer, a marketing person and a business person to handle large parts of the process. Most of my anxiety comes from money-related reasons.

How can neurodiversity be represented better in games?

Lisanne Meinen: It’s important to ask neurodivergent people to describe themselves early on in the design process and to get them involved. Or to do enough research and see how others describe themselves or the issues they face on TikTok for example.

Pierre Escaich: UKIE recently did a census and discovered that more than 18% of videogame developers self-ID as neurodivergent. So start by listening to your team members. I guarantee you’ll have neurodivergent coworkers.

Alan Jack: I haven’t seen a lot of good representation in media, but it’s important to add it for a good reason. It’s important that it brings something to the table and don’t just treat it as a cute way to make a character more relatable.

Are there any good examples of representation?

Pierre Escaich: For me, the best example happens in Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice and where her struggle with psychosis is represented really well. Videogames are very powerful. They allow you to walk in someone else’s shoes and live their experiences. Videogames as a medium can drive acceptance.

Alan Jack: There are some things we go through that can’t be broken down into a digital structure. So personally, I wouldn’t say games can be used to translate everything that is a struggle for us to other people.

Lisanne Meinen: The intentions can be good, and we can certainly aim for making others empathize with neurodivergent people through games. But don’t overestimate what games can do.

Pierre Escaich: I think the reason many of us flock to games or even TikTok videos about mental health, is because there aren’t enough specialists to help us all. There is a 2-year waiting period to get diagnosed. I know people who have been saved by discovering the source of their own anxiety by watching TikTok videos and games can do the same for some. I’m striving for positive representation of ADHD in any kind of media.

Would you mention your neurodiversity to your employer?

Coty Craven: I’m kind of hesitant to mention any disability before you’re hired for the job. Obviously, if you’re hard of hearing or need captions for your meetings, perhaps it’s good to mention the accommodations you’ll need ahead of time. It’ll depend heavily on the vibe you’re getting from the person or the company hiring you. The problem is we’re easily seen as the “difficult” or “lazy” people and that stigma can work against us.

Pierre Escaich: Disclosing or not is a personal choice. It’s illegal for employers to demand you to disclose your disabilities. If the recruiter or the company has no idea about inclusion, it’s possibly not going to be the right place for you anyway. A good recruiter will be looking for “culture add” not “culture fit”: how does the person in front of me help grow the team. An interview goes both ways: you are also interviewing the company.

Alan Jack: If you’re in a position to potentially turn down the job, you can comfortly ask yourself the question if this job is right for you. My crucade is focussing people on what matters and everyone should ask themselves what is most important. Is it important that the company is inclusive? Then ask them about it.

Any final words or advice you would like to share?

Lisanne Meinen: Neurodivergent people are extra vulnerable to explotation, if there is too much focus on results or the special skills and strengths you bring to the table. They’ll work extra hard to compensate, or they won’t know when to stop working.

Pierre Escaich: People who are atypical are experts in working outside of their comfort zone and this can be an advantage. Game development is exploring the unknown, permanently. The world around us, is not made for us, so we try and learn to adept.

And for neurotypical people, I would advise to listen. To ask questions. If someone tells you they are autistic, listen to their story. Never minimise their experiences, as it will seem like you don’t want to talk about it. Always acknowledge what they are sharing with you.

Alan Jack: Gamedevelopment attracts a lot of neurodivergent people because games are born from creativity, and creativity is born from diversity. I teach game design and what has become clear is that it all comes from motivation, how to motivate the player and drive them to act in a certain way and to have fun. So get to know what motivates people by listening to them.

Coty Craven: I think everyone is aware that the state of the industry sucks right now and this can be stressful, especially if you’re a neurodivergent student and the future is uncertain. Hopefully, knowing how many of your peers are in the same situation will make it less intimidating. But when you find your people, in the industry, you’ll make some of the best connections in your life.

About Game For Thought

Game For Thought (GFT) is a livestream series launched by Howest – Digital Arts and Entertainment (DAE) in collaboration with local medialab Quindo and sponsored by Vlaams Audiovisueel Fonds (VAF), it tackles ethically-relevant topics in the games industry and explores the impact & implications of industry developments. Each broadcast, Allie Weis, ethics coordinator at Howest DAE, invites a selection of industry experts to discuss the topic at hand.